A great journalist who

wanted to be

a journalist

By Jens Kruuse

Hans Christian Andersen, the brilliant writer with the sure eye, was one of the most travelled men of his time, and perhaps the best travel reporter.

"He never travelled without a long rope to save his life in case of fire"

Hans Christian Andersen was one of the most travelled men of his time. Hypochondriac, sickly, ailing, perpetually having toothache, he jogged his way through Europe, terrified by the slightest incidents, seeing robbers allover, and yet ever ready for the utmost exertions. He never travelled without a long rope with which to save himself in case of fire; and he would travel by routes not normally among those taken even by eccentric Englishmen.

The first journeys ( the earliest was in 1831) were partly a flight from criticism at home and partly were inspired by a longing to see something new.

But it was remarkable already then how he succeeded in making contacts, in finding the right, famous people. Despite his odd appearance, ungainliness and great sensitivity, he ventured to seek them out, and became their friend.

There were few if any European celebrities between 1831 and 1875 whom he failed to contact.

Chocolate with the Queen

In the longest period of his travelling life he bore himself like a prince among princes. A snatch of a letter will perhaps show what he felt of his fame (after the Bible, his books are the most widely read and translated in the world) when he compared himself as the fourteen-year-old Clodpoll from the lowest proletariat in the provincial town of Odense with now:

'Twenty-five years ago I arrived with my little parcel in Copenhagen, a poor unknown boy; and today I have taken chocolate with the Queen, sitting at the royal table right opposite her and the King.'

Note the 'little parcel'. Here we have his prodigious ability to see a detail and make it important.

We are dealing here with a travelling journalist. A figure of the same nineteenth century which fostered the great American and British travellers or the heroes of Jules Verne. A foreign correspondent! Hans Christian Andersen was that, too.

A letter from Hans Christian Andersen, written on notepaper of the Leipzig-Dresden Railway Company.

" I an like water: everything moves me, everything is reflected in me'"

Everywhere there is the same ability to fix an impression quickly and concisely. Here is a passage from the account of his first journey in Sweden:

'Did I not imagine Sweden half-barbarian, and Stockholm a city a couple of centuries back! Well, it is something quite different; it beats Copenhagen! The soldiers seem Prussian, the people Viennese, and the city's situation Neapolitan!'

In a letter of 1855 he characterizes himself as a journalist: '1 am like water: everything moves me, everything is reflected in me.'

Involuntary pressman

This brilliant reporter -for that was what he was- never had a fixed relationship with a newspaper. Indeed, with his tremendous sensitivity about whether others liked him, or appreciated him, he could not help having a poor relationship to the press in general. The slightest criticism grieved him.

One might almost say that as a journalist he was an involuntary pressman.

The term is based on the fact that Andersen's first journalism consisted of private letters, which their recipients found so interesting or lively that they straight away published them in newspapers or magazines.

One cannot be altogether certain that he did not occasionally envisage this possibility himself; but at any rate the first examples of this practice are definitely things that were not written with a view to publication. If we remember the character of the country and contemporary custom, this may be regarded perhaps as a handsome compliment.

Nor was the young Hans Christian Andersen altogether innocent of his journalistic debut. He was travelling between two Zealand towns (Slagelse and Elsinore), accompanying his headmaster who was preparing him for university. On arrival, he wrote letters to acquaintances about the journey. And he was so pleased with the letters that he copied them from the first.

Now, at this time Andersen was quite in the hands of his wealthy benefactor. He had been obliged to promise not to write until he had passed his examination. So it was a calamity for him that his letter was quickly published in a paper read by the cultivated public.

It was actually a distinguished man of letters and learned professor (Rasmus Nyerup) who had caused it to be printed. though unsigned. But everybody in the small inner circle of small Copenhagen (several of whom had received the letter themselves) knew that it was Andersen who had written the article headed 'Part of a Journey from Roskilde to Elsinore'. Andersen could only protest his innocence. He had merely

'The harem lay dark-red, the barred windows gleaming of silver and gold '

written letters, he explained to his strict, good, fatherly bene factor. 'So it is there without my knowledge, and quite against my will. ..' That was how Andersen, one of our most brilliant travelling journalists, tumbled backwards into journalism.

'While there is no signature to it, it nevertheless annoys me that it has been printed.... he says in his letter of apology .But that can scarcely have been entirely true. His debut as a read, printed author in the capital! A great moment. And it was as a journalist.

Andersen wearing a fez, a souvenir of his adventurous travels in the Near East. Drawing by Christian Hansen.

We must quote from the report. Andersen had to pass through Slangerup, birthplace of the poet Kingo. "Spute Dich. Schwager Kronion! (Hurry up, you slowcoach!)", I shouted to our driver, and at last Slangerup church tower came into view behind the green hills. It was fast, and at length I came, I saw, I found- a "hole". I had expected a neat little town, and I saw a wretched village; we could not even get a stepladder at the coaching house to dismount, the ladies having to balance themselves on the back of a chair, stared at by the young locals who lay in picturesque groups in the neglected ditches, gazing into the wide world.'

Theatre report from Paris

His first appearance as a reporter with some sort of an assignment was in the respected paper Kiøbenhavns-Posten. That was on June 22, 1833, and the occasion was a letter from Paris; again unsigned, and seemingly private.

But one can see it had been written for an audience (for which indeed there is separate evidence), as it is full of snippets of news of the kind later to become general in papers allover the world. The striking point about this first semi-professional bit of journalism, as I see it, is that he appreciates -as a good reporter must -that his readers want information, many short, well-turned items -facts.

He is still the inspired writer with the sure eye. He thinks of the locals at home: 'Herold's latest opera is a sea of tones with storm and calm; it is admirably suited to our stage. ..' Or he describes the piquant in fine form: ' As proof of the loose tone which prevails in most new vaudevilles, and of which we have no conception, one of the newest, Sous Clef, which is played by a single lady, can be cited. She is shut up; her lover cannot get in. She eats and drinks, sings amusing couplets, and finally undresses to the last article. At that moment a small window above the fireplace opens; the lover has found his way through this and leaps out. The girl utters a scream and dashes into bed; the lover approaches quite silently- and the curtain falls. It's a great success!

What theatre reporting: exhilarated, titillating and with the observed detail 'the lover approaches quite silently'!

Andersen's two greatest achievements as a travelling journalist are collected in book form; but they are articles. The first and most colourful is A Poet's Bazaar, which describes a tour of the Near East, unique in view of the contemporary conditions and the writer's little personal courage.

Here is a scene from Constantinople: 'The harem lay darkred, the barred windows gleaming of silver and gold.'

In this series of articles the accounts of the journey along the Danube and through rebellious Bulgaria and of a period of quarantine on the Austro-Hungarian frontier (ten days of unpleasantness) are climaxes of a journalistic feat unexcelled even by Jules Verne's travelling reporter on the Trans-Siberian Railway.

The other travel book consists of articles about Denmark's unknown neighbour, Sweden. It is perhaps his most successful, but, in away , it is perhaps literary theft to class it as journalism.

In time his relations with the press became peculiar. He

was extremely touchy, and could display hatred of the newspapers for their criticism, particularly of many unsuccessful dramatic efforts. " I saw a woman carried off by the current "

, Not to be printed'

It is more interesting to note that at the pinnacle of his fame he refuses to submit to being used as in the early days. He wrote many letters to friends, also when he went abroad, planning a travel book. But he would occasionally head them: 'Not to be printed! ,

It was not always effective. So we can see one letter as a piece of first-class reporting. It is partly an account of a flood in Barcelona. The following quotation will reveal him as an unsurpassable journalist; and one can appreciate his annoyance at seeing it used in a newspaper he had no wish to write for.

'Streams and rivers from the mountains had burst all the dams, swept away the railway, transformed the road into a river which surged with such tremendous speed into the city itself that it carried heavily loaded vehicles with it; the water rose in an instant to the windows on the ground floors, and shop signs, beams, melons and torn-up cactuses drifted about everywhere. The smaller streets looked like rushing millstreams. I saw a woman carried off by the current; three men went in up to their knees and got her out half-dead. The priests in church saying mass stood up to their waist at the altar.'

Here again is the journalist who succeeds in presenting the whole through the detail; the melons, the woman and the priest bring us close up.

He also wrote from Portugal for the press, this time of his own free will. Here is a brief glimpse:

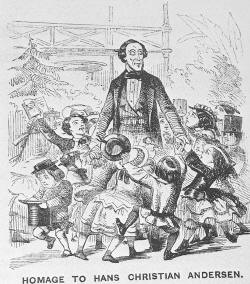

Cartoon from Punch, 1857.

, ...the higher we got, the richer the vegetation got. Here grew in plenty a sort of thorn-less pink rose, a profusion of heather, a wealth of unfamiliar flowers and strongly scented foliage. But road and path vanished completely, the stones rolled before the donkey's feet; the ascent was difficult, , His style comes like sunshine , or like the crack of a whip!' always led and urged on by Carlos, who several times was about to fall, and who kept on jabbing the barrel of his gun into my face. " Is it loaded ?" I asked. "Yes," he replied. ..'

Visiting Charles Dickens

On one further occasion a private letter, this time about a visit to England (where he stayed with Charles Dickens) was used by the press. He had been rash enough to write it to an alert editor, who amusingly wrote back: 'You will have to put up with my using your letter for my paper; an editor goes about like a roaring lion, quaerens quem deboret (asking whom he can devour) , and you have put yourself in front of the open jaws.'

It was a lively piece of reporting, covering among other things the first Handel festival in the Crystal Palace and life with Dickens at Gad's Hill.

Hans Christian Andersen was a great journalist, who would never be a journalist.

But he would write, and indeed behave, like a journalist of the rarest sort.

One of Denmark's few really outstanding literary critics in the first half of the century put most clearly what has been said about the fairy-tale writer as a journalist. He was writing about the travel letters from Spain, and we will conclude this article by quoting him. He wrote:

"His style comes like sunshine, or like the crack of a whip!"

Andersen's very private diaries, written only for himself, are at present being published in Denmark. They make wonderful reading. But a professional journalist would hardly have squandered such rich reporting on himself alone.

The author: Jens Kruuse, born 1908, dr phil 1934. Assistant professor, Danish language, Paris 1934-38; assistant professor, comparative literary research, University of Arhus, 193942; assistant professor, dramaturgy, 1970-74. Journalist and literary critic of the Jutland daily Jyllands-Posten since 1942. Author of several books and essays on literary history.

|